Are we missing the role of Chief Intelligence Officer (CINO) in management?

How can a new CINO role improve the quality of decisions in management teams?

Written by:

The answer likely depends on a number of prerequisites. To what extent do companies actually utilise intelligence for strategic decisions? How can they, if at all, make the organisation able to utilise intelligence? And what competitive advantages would a central intelligence function provide?

TL;DR

This blog post addresses common misunderstandings about the nature of intelligence, the differences between intelligence and cybersecurity as distinct fields, and how this affects decision-making in the private sector.

The blog post claims that the intelligence domain is significantly underutilised in the private sector, and suggests that establishing a role dedicated to this within management could be beneficial in many organisations. With increased digitalisation and a more comprehensive threat landscape it is likely that a large number of organisations could be in need of this role.

A central intelligence function, for instance in the role of a Chief Intelligence Officer (CINO), could assist decision-makers to get a better overview of what matters for their particular organisation and what is just noise, as well as interpreting information through the eyes of their organisation.

To explore what this role could look like and what challenges would be associated with the CINO role, we’ve conducted several interviews with a variety of Norwegian business executives, intelligence analysts, and security professionals. These interviews provided insights into what these organisations think is missing currently, and what needs they could see being met by a CINO role.

Background

In 2021, A.J. Nash wrote "Rise of the Chief Intelligence Officer (CINO)”, an article that examines the challenges faced by Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI) within private organisations in the United States. Despite the presence of CTI resources in many large corporations, there is often a lack of required intelligence expertise, standards, and processes to assist decision-makers beyond technical detection tools and reactive strategies. Nash believes this is because of a fundamental misunderstanding of the true nature of intelligence, and the difference between intelligence and cybersecurity as separate disciplines.

This trend is not unique to the United States. In Norway as well, more and more organisations have either used consultants or hired their own CTI resources. These resources are frequently integrated with a Security Operations Center (SOC), with a focus on detection and incident response. While these resources are undoubtedly valuable for detecting incidents and providing decision support during events, this approach does not take advantage of the full potential of the intelligence discipline.

Narrow Intelligence practices in the private sector

The potential within the intelligence field is in reality much more comprehensive. There are countless definitions of what intelligence is and should be, but most definitions paint a picture of something broader than what appears to be the common practice within CTI today. Adapting the Norwegian Armed Forces’ definition into a civilian context, intelligence can be understood as the result of the collection, analysis, and assessment of data and information, used to provide an advantage in decision-making processes. In other words, intelligence is decision support. This involves providing an advantage in all types of rational decisions related to an adversary, at all levels within an organisation.

Need for change

The private sector has a need for robust intelligence capabilities. With the rise of digitalisation, the threat landscape is becoming increasingly intricate. Macro factors such as geopolitical tensions, inflation, and climate and energy crises add layers of complexity. Beyond threats, these dynamics also influence an organisation's strengths, weaknesses, and its opportunities. What competitive edge could effective decision support provide an organisation navigating this landscape?

Decision-makers, despite having access to large amounts of data, are challenged with gaining an overview of what is in fact important to their organisation, what is just noise, and interpreting the true meaning of the information they have access to. Targeted information gathering and analysis are vital to prevent being overwhelmed by noise. This also includes information generated within the organisation itself. The capacity to tap into the organisation's collective knowledge base is key to informed strategic decision-making.

To illustrate the broader application of intelligence, consider a company venturing into a new, unfamiliar market. Existing intelligence processes could be integrated into the market analysis, enriching it with a broader base of information and additional analytical methods. Systematic hypothesis testing, defining specific information requirements, and focused information collection could mitigate uncertainty in evaluations. Coupled with clear communication of findings, this could strengthen management's confidence in their strategic choices.

These use-cases show some of the untapped potential of the intelligence field. Yet, a critical question is yet to be unanswered: who within the organisation is tasked with unlocking this potential? As a solution, Nash suggests to create a central intelligence management function reporting directly to the leadership. He names this role a Chief Intelligence Officer (CINO). This role is designed to, among other duties, utilise the advantages of being part of the executive team, to forge a comprehensive intelligence perspective, coordinate information needs, and standardise methodologies and processes. The aim is to provide management with robust support for strategic decision-making.

Since the publication of the article, the CINO model has been attempted by several American companies. In discussions with Nash, he indicates that the implementation has proven difficult and has achieved mixed results. Given the American experience, it might be tempting to set the whole concept aside and wait for more favourable outcomes. Or, we can take a more proactive approach, and contribute to the continued development to the model, closing the gap between untapped potential and existing needs. The model is under development, and must go through a maturation process.

This prompts the question: could the CINO model, or a similar role, improve the decision-making processes within Norwegian organisations? To get closer to an answer, we have conducted interviews with a range of Norwegian business executives, intelligence analysts, and security professionals. In the interviews, they shared their perspectives on what their organisations are currently missing, and what needs they could see being fulfilled by a CINO role.

The interviewees come from large, well-established organisations in various industries, including finance, technology, energy, and communications. The interviews were semi-structured and are not considered scientifically rigorous. The findings all shed light on a core challenge: how does an executive know that he or she is making decisions based on the best possible information?

Observation 1: There is a widely recognised need for closer integration between risk management and intelligence functions

Strategic decisions are typically grounded in risk assessments. Could an increased integration with intelligence functions improve the efficacy of risk management practices?

All interviewed organisations have a focus on risk management and make strategic decisions based on risk. There is a broad consensus that risk management is beneficial for creating comprehensive and comparable decision-making foundations across different disciplines. The organisations also have a set of functions, roles, and responsibilities related to risk management. Some have a centrally placed function, such as a Chief Risk Officer, while others partially delegate risk management to various business areas.

Several organisations with dedicated CTI units have also acknowledged the necessity to integrate threat intelligence into their risk management processes. This need has been identified across multiple business sectors, including both CTI and risk management functions, and at various levels of decision-making. CTI units often lack insight into management’s information needs, feeling as though they are dispatching reports into a void, receiving little, if any, feedback from the recipients. On the other hand, recipients of these reports face difficulties in leveraging this information.

It appears to be a gap between what is considered the ideal way the organisation should function, and the current state. This gap is primarily found in the areas of risk management, security, and intelligence functions. In the ideal scenario, processes benefit from interaction between different teams and departments, without this having negative consequences for efficiency. The aim of these processes is to guarantee that accurate information is delivered to the appropriate decision-making level at the correct time, providing a strategic advantage in the decision-making process.

Current initiatives to close the gap between these groups are currently unsuccessful. None of the interviewees have discovered an optimal model for collaboration. Additionally, there is a commonly expressed desire for an established "best practice" to serve as a reference point. Nevertheless, some have developed working methods that appear to fulfill the need for more integrated approaches. For instance, processes for translating threat intelligence into financial language and implementing roles that serve a coordinating function.

Finding 2: The challenges with the CINO concept are also present in the Norwegian context

While the CINO concept could theoretically provide advantages for an organisation, it appears to be several barriers to achieving this. Nash and the Norwegian organisations interviewed agree on three primary challenges:

First, the creation of a new C-level position will lead to shifts in power dynamics and decision-making processes within the organisation. Nash cites resistance to such change as the main reason why attempts to establish this role have not been successful. A potential (perceived or real) overlap with existing roles, such as the Chief Information Officer (CIO) or Chief Risk Officer (CRO), may generate internal opposition to the new position.

For a Chief Information Security Officer (CISO), the introduction of a CINO could be seen as a diminishment of their control over intelligence resources. Additionally, if the initiative originates from CTI functions that are currently subordinate to the CISO, it might be viewed as motivated by personal career aspirations. Considering that the implementation of a CINO represents an organisational change, change management is likely to be a key factor for success.

Secondly, it will be challenging to provide good evidence for a positive cost-benefit outcome before establishing the new role. The lack of precedents and tangible case studies creates uncertainty. Additionally, similar to other areas of the security field, it will be difficult to establish suitable metrics to measure success. There is a recognised paradox in security and intelligence that it is often impossible to prove that negative events would have occurred without targeted preventative measures. Consequently, management must be willing to tolerate a level of uncertainty upon establishment, with the understanding that they might not be able to measure the benefits accurately even when the function is active. This inherent uncertainty can make it difficult to justifying the new role.

The last major challenge is tied to the question of whether a CINO role requires a certain level of organisational maturity, specific structural configurations, or a distinct corporate culture. Although the interviewed companies express a desire for a "best practice" model, there is also fear of the concept being too rigid, not aligning with the current organisation or requiering to many organisational changes. The interviews indicated that many companies consider themselves too immature to implement the changes to their line functions and decision-making processes.

This challenge also revolves around methodology. A concept that dictates particular intelligence methods, such as the ones derived from national intelligence services, might be in conflict with the need for tailored solutions and diverse approaches. During the interviews, there was different opinions regarding the appropriateness of military intelligence methodologies for the private sector. The concerns centered around these methods being perceived as overly extensive, too rigid, and demanding in terms of resources.

Finding 3: A flexible approach may be the way forward

This blog post does not seek to prescribe definitive solutions to the challenges identified. Instead, it aims to contribute to a discussion that may help get us further down the line towards a practical solution.

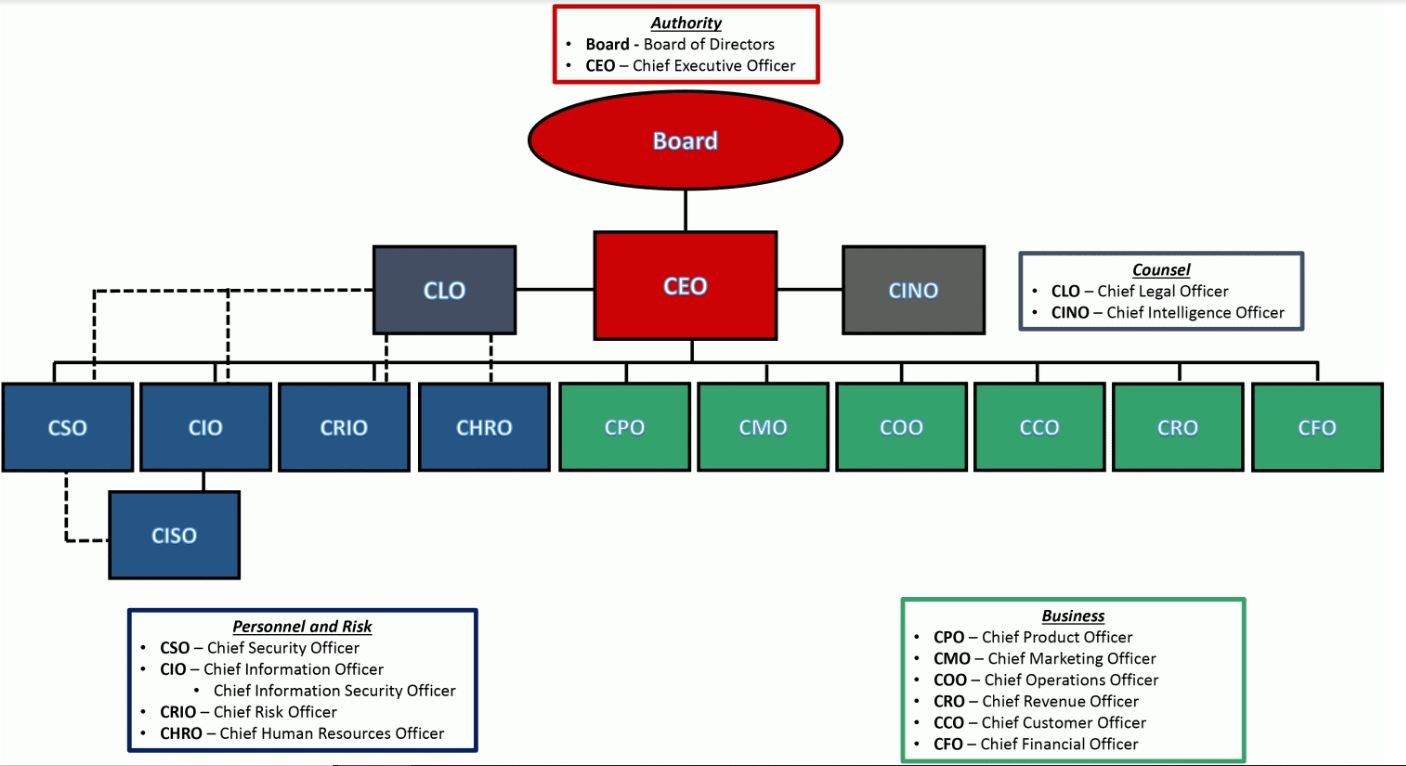

While Nash's article presents a single model for the CINO role, the insights from the interviews lean towards the likelihood that there is no universal "one-size-fits-all" solution. The organisational model illustrated in Figure 1 might be a logical objective for some companies, but not universally applicable. Certain organisations may choose to maintain a smaller executive team, while others may prefer to expand their existing roles and mandates. To effectively meet the challenges discussed, it is probable that tailored solutions specific to each organisation will be necessary. This opens the possibility for developing a more flexible framework for the CINO function.

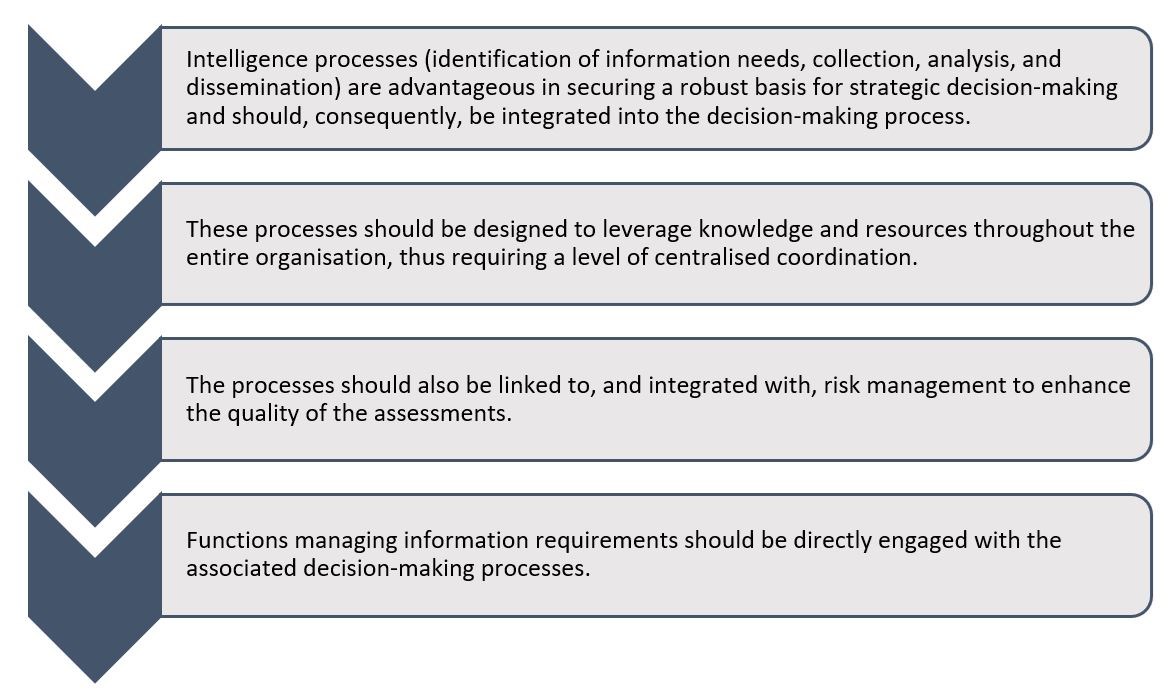

The interview findings suggest that Norwegian companies broadly agrees on a number of statements – or goals – that are associated with the role of a CINO. The key ones are:

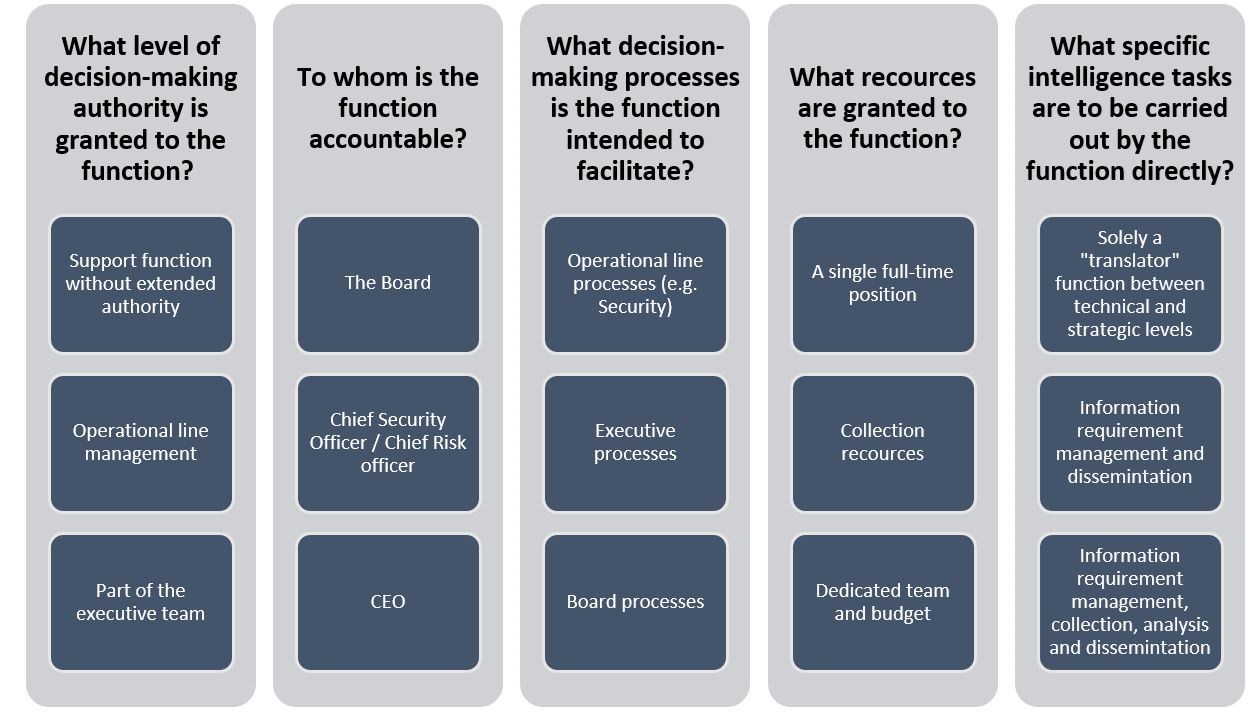

An organisation that agrees with these statements and wants to create a central intelligence function should discuss these strategic directions to adapt the role to their organisation and goals. The following questions highlight a range of defining variables. Rather than prescribing a single "best practice," we offer examples of different directions to demonstrate the breadth of available choices.

The responses to these questions will form the basis for how an organisation tailors its solution. Some combinations may prove to be impractical in reality (for instance, it would be impractical for a function with fewer resources to independently manage a complete set of intelligence processes), while other combinations could serve as a catalyst for the function's gradual expansion or for rethinking organisational structures.

The model's flexibility could make it more approachable for smaller organisations. While mature and well-resourced enterprises may need a broader range of options for their implementation model. Even startups can find value in working towards these goals. A good basis for decision-making can be just as valuable for a CEO in a small company in growth, as it is for a manager at an established market-leading organisation. In this sense, a central intelligence function - even with limited resources - can be a good investment.

The way forward

There are a lot of different initiatives that could enhance the way intelligence expertise is utilised in the private sector. Organisational measures are just one aspect of this and are not an end in themselves. However, the adjustment of organisational structures seems to be a measure that can have substantial benefits.

We believe that senior executives, intelligence analysts, and organisations as a whole would gain from integrating intelligence functions more closely with the executive team, to give support for strategic business decisions. The concept of a central intelligence function – potentially in the form of a CINO – is worth considering. This is a sentiment we share with other established enterprises in our community. The simplified model above can be further developed into a framework that can make implementation easier.

Nonetheless, we recognise that various challenges associated with the CINO model must be addressed to avoid friction. A more adaptable model could help with that. For this reason, the decision and, preferably, the initiative to implement should originate from management. Consequently, an important task moving forward will be to inform executives about the value of a central intelligence function and, more precisely, how intelligence can enhance strategic decision-making. If only there were someone with intelligence expertise in close proximity to the C-suite...

Get in touch